The Background to Hitler’s Supercars

Nazi Germany was nothing but the evil, chaotic manifestation of one man’s ego. That man was Adolf Hitler.

Consumed by a rabid hatred for anyone or anything they considered to be “lesser”, Hitler and the Nazis took power on a wave of nationalism in 1933. In the years running up to World War II, they were on a mission to restore German national pride after the country was - at least from their perspective - stripped of its dignity after World War I by the Allied forces.

To contextualise the story of Hitler’s Supercars - a documentary which will air at 20:00 GMT on July 26th on Channel 4 - the Allies forced Germany to sign the Treaty of Versailles in the aftermath of WW1 for its role in the conflict. It stripped the once-proud nation of its armed forces, and to add insult to injury Germany was also made to pay 132 billion marks in reparations and concede vast swathes of its territories across Europe.

The Great Depression of the late 1920s and early 1930s was the final nail in Germany’s pre-Nazi coffin. The country was financially on its knees and the mass-poverty, national malaise and economic hardship were a major factory in the Nazis coming to power: Jews were demonised for the country’s ills, and the Nazis’ idealistic rhetoric of building a bigger, better, brighter Germany appealed to the masses.

Hitler’s vision was a Germany which had the world’s brightest and best engineers; a Germany where every family would own a car, and a Germany whose technological and military superiority would ensure that the country would never again have to suffer the humiliation it felt at the hands of the Allies after WW1.

There was a catch though. The Versailles Treaty stipulated that Germany had to disarm to prevent it from starting on its neighbours again. However, this didn’t stop Hitler. In 1935 - after which he had disposed of the opposition during the Night of The Long Knives and assumed full dictatorial control of Germany - he unveiled an all-new military which would be used to devastating effect across Europe in the opening years of World War II.

But whilst Hitler was secretly building up his new military, he needed a medium he could use to show the world that Germany was back. Hitler wanted to show that his Germany was serious in its ambitions. Very serious.

Hitler was imprisoned for writing Mein Kampf, and whilst behind bars, he developed an obsession for cars. On his cell walls, he was reported to have made the sketch for the original People’s Car, which - under the guidance of Ferdinand Porsche - would become the Volkswagen Beetle.

Seething over Germany’s supposed humiliation after World War I, Hitler was also gripped by a desire to use automotive engineering as a way to assert dominance over those who had stripped Germany of her dignity.

Goebbels’ Use of Motorsport as Way of Winning Over Weary Hearts and Minds

Fast-forward to May 1932, and Hitler had found his muse: motorsport. The AVUS Grand Prix in Berlin was won by homegrown-hero Manfred von Brauchitsch in a Mercedes-Benz SSKL.

The howling, supercharged machine boasted a streamlined body, which made the rivalling Bugattis and Alfa Romeos seem almost agricultural in their appearance. It was like nothing the motorsport world had seen before.

For a country as weary as Germany was at that time, Von Brauchtisch’s home Grand Prix win behind the wheel of a German car was the perfect way to cheer up a weary nation. It was also an opportunity Hitler seized upon to lead the public to believe that Germany could become great again.

When Hitler was elected as Chancellor the following year, racing cars - for now at least - would become the new weapons. At the same time, his Macchiavellian spin doctor Dr. Josef Goebbels also jumped on the opportunity to transform the airwaves into the equivalent of today’s 24-hour news cycle.

It is this combination of Goebbels’ PR nous and the Nazis’ use of the racing car as a show of national strength that piqued the interest of Jim Wiseman - the writer and director of the upcoming Hitler’s Supercars documentary. He has also previously worked on Channel 4’s Formula 1 coverage and Clarkson-era Top Gear.

“The whole idea for Hitler’s Supercars came about after I read a piece about the world’s fastest race cars in Motor Sport magazine,” he told Dyler.com. “The feature also included an image from the 1937 race of the Auto Union streamliner Type C car going around the banking at the AVUS, and I just thought it looked properly cool. There were Nazis everywhere too, so obviously I went down the Google wormhole and came up with the idea for Hitler’s Supercars.

“I was initially a bit sceptical because the title ‘Nazi Supercars’ sounds a bit like a B-Movie, doesn’t it? I mean, in recent years there’s been Nazi Megastructures, Nazi this, Nazi that, so I wouldn’t have blamed our distributor if they decided to say no to our pitch. As it turns out though, they said that World War II and Nazi stuff always tends to go down well, so here we go!

“There’s a lot of appeal in the cars because they look properly cool. They look like nothing before or since. What I found equally interesting though, was how the Nazis - and especially Josef Goebbels - really took motorsport and shaped it into an enthusiast’s sport that the nation could really get behind. Don’t get me wrong though, Goebbels was an awful piece of work. Just like Hitler, he was one of these small angry men who just wanted power at all cost and he used the country’s Grand Prix successes to amplify the regime’s successes and get off on his own ego.”

Motorsport was an easy propaganda victory for the Nazis. In 1930s Grand Prix racing, the German drivers were dominating and raced up race win, after race win. The imposingly tall Mercedes-Benz driver Rudolf Caracciola won three drivers’ championship in 1935, 1937, and 1938, whilst dashing Auto Union ace, Bernd Rosemeyer, won the 1936 title. As the Nazis’ on-track success grew, so did nationalist sentiment along with Hitler’s desire to further showcase Germany’s technical prowess and the superiority of the Mercedes and Auto Union cars and drivers.

The Battle for the Public Road Land Speed Record and the Creation of the World’s First Ground Effect Race Car

After an immensely successful Olympic Games in 1936, Goebbels used the opportunity to shout even louder about Nazi Germany’s motorsport achievements.

Not content with their cars dominating the Grand Prix calendar, Nazi top-brass started the short-lived ‘speed week’ - a way of ramping up the competition between Auto Union and Mercedes, and a platform for showcasing the excellence of Nazi engineering.

The speed week ran until 1938, and took place between Grand Prix seasons. Its premise was simple: both Mercedes and Auto Union would try to record the fastest possible speed over a quarter-mile stretch of the newly-built public autobahn network. The winning car would then gain national racing car acclaim from Hitler himself. In short, it was a competition to become the Fuhrer’s Favourite and earn the title of the fastest car in the world.

“The cars used from 1937 in the public road land speed records are proper, proper silly, but they are still astonishing pieces of engineering,” Wiseman continues. “The Mercedes-Benz W125 Rekordwagen was an adaptation of the W125 that the Stuttgart manufacturer had used to win six from 12 races in the 1936 Grand Prix season. Its open-wheeled layout had been highly modified for its record attempt, and the W125 Rekordwagen now had a low-drag, closed-wheeled body that was developed in a wind tunnel used in the design of zeppelins.

“The Mercedes engineers also worked out that a regular air-cooled engine would have been counterproductive to their record attempt, so they ensured the radiator was stored in a ice-filled chest built into the car to keep temperatures as low as possible. They also did away with the original car’s inline eight engine, and replaced it with a thunderous 736bhp V12, because it had more power, and could be mounted lower down in the car for a lower centre of gravity.”

With Caracciola at the wheel - a man who had already won two Grand Prix drivers’ championships - Mercedes had taken the first swing in the fight for automotive supremacy in Nazi Germany.

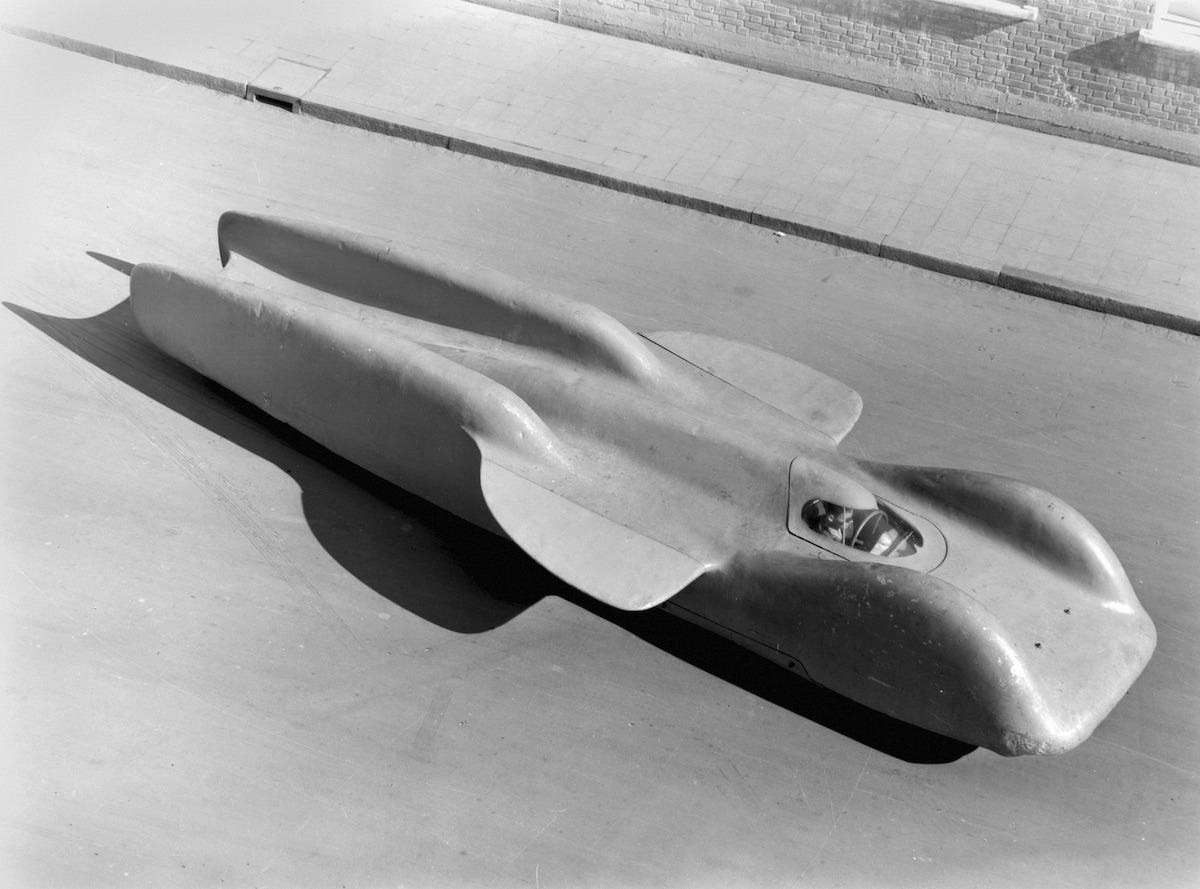

In their efforts to become Hitler’s favourite car manufacturer and not be outdone by arch rivals Mercedes, Auto Union threw everything they had at their speed record car - the Auto Union V16 Streamliner.

Derived from its Type C Grand Prix racer, the Auto Union V16 Streamliner was the world’s first ground effect racer - albeit in a very rudimentary form. Auto Union engineers worked out that ground effect - a phenomena that sucks the car to the floor and increases downforce as it gathers speed - would help it beat Mercedes in the pursuit to become Germany’s fastest car manufacturer with the country’s quickest driver behind the wheel.

To put into perspective about how technically ahead of its time the V16 Streamliner was, there would not be another ground effect race car until Lotus launched its revolutionary Lotus 79 Formula 1 car 40 years later.

Tragically, it was the Nazi pursuit for technological superiority that led to Rosemeyer’s death in 1938. Aged just 28, he was killed during a land speed record attempt on a flying mile run along the Frankfurt to Darmstadt autobahn.

Auto Union’s Bernd Rosemeyer and the Power of Celebrity

Before getting to Rosemeyer’s ill-fated speed-run, it is important to understand just how much of an important role he played in the Nazis’ creation of national heroes.

Rosemeyer burst onto the Grand Prix scene in 1935 aged 26. Charismatic, good-looking, and - albeit reluctantly - a member of the elite SS paramilitary organisation, he won the hearts and minds of the German public after almost winning his second ever Grand Prix from Caracciola’s Mercedes. It was only a missed gear that denied the Auto Union driver in the final lap of the race.

Rosemeyer’s star was sealed by his marriage to Elly Beinhorn - a German aviator who was easily as famous as her contemporary, Amelia Earhart. The fact the young driver met her on the podium of the 1935 Czechoslovakian Grand Prix - a race he had just won - also contributed to their status as one of Nazi Germany’s first bona-fide celebrity couples.

“One of the things I really wanted to touch on in Hitler’s Supercars was Bernd Rosemeyer’s role as the ‘golden boy’ of Nazi Germany’s motorsport efforts,” explains Wiseman. “But to understand this, we need to understand how the Nazis used radio as a medium to influence the masses.

“Goebbels once famously said to “think of the press as a great keyboard on which the government can play,” which is exactly what he did when he commissioned the mass-production of these cheap little radio sets in the early 1930s. The bandwidth on these things was utterly awful, so you could get what was basically Nazi FM and not much else. The government-controlled message of Germany’s superiority in motorsport and everything else was also a 24/7 news cycle that constantly poured into the ears of millions of people across the country, so of course people were easily taken in by the Nazis’ given the national mood before they came to power.

“Combine this with Rosemeyer’s celebrity status and Germany’s domination in Grand Prix racing which was also massively covered in newspapers, and you’ve got a winning formula that will make people turn up to these races to watch their heroes in action. The Nazis then noticed that a motorsport event was a great excuse to show the population how much they were winning as a political entity, so in addition to the race, they’d put on a light show, wheel out the swastikas, get the top-brass to give some speeches and use it as an excuse to have a rally and give it large.

“In short, a Grand Prix became a Nazi rally with a sideshow of motorsport, and if you look at some pictues from these events, they look very seductive given that people had pretty much nothing to look forward to just a few years before hand.

“It’s also important to remember that Hitler used the radio and the press as a way to divide and rule the Auto Union and Mercedes fans over the airwaves and in print, which is how he basically did everything. The rivalry between Caracciola and Rosemeyer was painted as something bitter, but it couldn’t have been further from the truth. In fact, when Rosemeyer was killed in 1938, Caracciola was deeply affected by his friend’s death. I think this is just another example of how twisted the Nazis were…”

Hitler’s Exploitation of Rosemeyer’s Death in the Pursuit for the Ultimate Land Speed Record

However, the land speed record was a matter of national pride and Rosemeyer was determined to bring it home for Auto Union. In the high-sided V16 Streamliner, Rosemeyer took to the autobahn to have one final attempt at beating Caracciola’s 268.8mph in the Mercedes. In his previous run, he’d recorded a 266.5mph - fast, but given the competitive nature of the racing driver, not fast enough.

With his vision blurred and feeling winded as a result of the ground effect sucking the car to the ground, Rosemeyer threaded the car down the narrow black stretch of autobahn to a maximum speed of 269mph. Whether it was a gust of wind or disintegrating panels that came as consequence of the enormous forces exerted on the Auto Union’s lightweight bodywork, Rosemeyer lost control of his machine.

The disturbance caused a loss in the ground effect and unlike modern day racing drivers who are well-prepared to cope with the potential loss of vacuum from a ground effect car, Rosemeyer simply wasn’t because of the technology’s infancy. After trying to correct the slide in the classic ‘turn in and add power’ way, the Auto Union veered wildly out of control. Experts claimed afterwards that the snaking tyre tracks that followed the wreck veered violently to the left, then the right, and finally into a grass bank. The car then somersaulted through the air, and sliced through several trees and a stone milepost.

During the accident, Rosemeyer’s unmarked body was thrown 23 feet from the mangled car. He was just 28 years old leaving behind his wife and their two-month-old son. The crash site is marked today by a small wooden memorial.

Rosemeyer’s incomplete run meant his speed was not officially counted as a record. The 268.9mph set by Caracciola and the Mercedes W125 Rekordwagen was the one that mattered. Until 2017, it remained the fastest speed to ever be recorded on a public road.

“It might be a bit controversial, but I think it’s fair to say that Rosemeyer’s death can be compared to that of Ayrton Senna,” Wiseman says. “When Rosemeyer was killed, he was literally at his peak as a race driver - he was winning races across the world and he was married to Elly Beinhorn who was a celebrity in her own right. He was an absolute superstar. It’s fully understandable that his death sparked a national outpouring of grief.”

Rosemeyer’s death should have stopped the land speed records. Germany had lost its star driver, and Auto Union had decided that things “had got properly silly”. Unsurprisingly, it was reluctant to engage any further in the competition.

But things didn’t stop there. In their continuous pursuit for dominance and superiority, Hitler and the Nazi propaganda machine used Rosemeyer’s death as a PR stunt. Despite the reluctance of his widow, Hitler gave Rosemeyer a state funeral with full SS honours, and Hitler hailed the young driver a hero who died for Germany’s glory.

After having set the world record for the highest speed on a public road, the Nazi party’s lust for more motorsport milestones swelled. Rosemeyer’s death and hero status was used by the Nazis as a pretext to pursue his next ambition - the annihilation of the outright land speed record. Ironically though, it wasn’t Hitler who came up with this idea - it was his old friend and former Auto Union racing driver, Stück, who had originally suggested it.

The Mercedes-Benz T80 - Hitler’s Personal Project and “Peak Nazi”

At the time the Nazis decided to go for the outright land speed record, the achievement was held by Briton’s John Cobb, who recorded a speed of 367.91mph in August 1939.

The Mercedes T80 was the car that was set to destroy the land speed record. This astonishing piece of design by Dr. Ferdinand Porsche is a machine Wiseman describes as “peak Nazi”. The project was overseen by Hitler himself, and those involved read like a who’s who of Nazi Germany’s motorsport elite.

The twin-tailed car’s protruding wings hint at a solid understanding of downforce amongst Nazi Germany’s finest racecar engineers, and at over 27 feet long, the six-wheeled T80 was bigger, longer, and lower than anything that had come ever before. With an aerodynamic coefficient of just 0.18, the T80 is still more aerodynamically efficient than the most drag-efficient Mercedes’ production car available today.

Porsche calculated that the T80 would need 2,500bhp to break the land speed record. However, Cobb’s accomplishment made Hitler incandescent with rage. The Führer ordered that his favourite engineer squeeze an additional 1,000bhp from the 44.5-litre V12 that Mercedes had taken from the Messerschmitt Me 410 fighter bomber and dropped into the back of the T80’s carefully sculpted body.

The T80 was to be driven by Stück who would take the car to a predicted land speed record-breaking speed of over 400mph - a speed that wasn’t reached until the 1960s. Just like the streamliners that had come before it, the T80 was lightyears ahead of its time.

As a final middle finger to the countries Hitler felt had kicked Germany around after WW1, the T80 was to be painted in the national colours of red, white, and black featuring swastikas and the Nazi eagle crest.

Yet this astonishing display of hubris and feeling of invincibility is why the T80 remained a stillborn project. By the time Hitler’s ultimate supercar was scheduled to run in February 1940, the Nazis had already attacked Poland and WW2 was well underway.

The T80’s monstrous V12 was returned to the Luftwaffe, and the country’s top race car engineers were reassigned to the war effort. To this day, the T80 has never run, and it now serves as a showpiece inside the Mercedes-Benz museum in Stuttgart.

“The T80 came at a time when the Nazis were at their absolute peak,” concludes Wiseman. “However, at this time, they began to believe their own hype of invincibility which is why they were starting on their neighbours left, right, and centre and eventually caused another World War.

“Without a doubt, these Mercedes and Auto Union cars were, and still are amazing pieces of engineering which were about 40 years ahead of their time. At the end of the day though, they only came about because Hitler was a pathetic racist who wanted to seek revenge on the nations he felt had kicked Germany around after World War I. Until he started picking on everyone, he thought that getting his top boys together to create a car that would smash the existing land speed records to bits would be the best way to achieve this. They had absolutely no doubt in their ability.

“However, it was this supreme arrogance that led to the T80 becoming one of the greatest ‘what ifs’ in automotive history.”

To find out if the Nazis would have succeeded in setting the outright land speed record with the Mercedes T80, tune into Hitler’s Supercars on Channel 4 at 20:00 GMT on Sunday, July 26th.

---

Find your dream car among our Car Categories!